A series of earthquakes in West Texas’s Delaware oil basin could be the result of oil and gas industry’s wastewater operations in neighboring New Mexico.

When oil and natural gas are extracted in the region a byproduct known as produced water is brought to the surface from the same underground rock formations where oil and gas is extracted from. Scientists estimated up to 10 barrels of produced water are generated per barrel of oil. A barrel is about 42 gallons.

Traditionally, the toxic and brackish water is pumped back underground into the formations, but recent research suggested this could induce earthquakes and seismicity in the same areas the water is reinjected.

But the connection between New Mexico’s water and Texas’ earthquakes can be murky, said Adrienne Sandoval, director of the State’s Oil Conservation Division, due to a lack of data on the actual origin of the water both in her agency and at the Texas Railroad Commission.

“In terms of movement of tracking New Mexico water over the border to Texas, we don’t track that. We do hear that water from New Mexico could come over to the Texas side,” she said. “The specificity of where the water comes from is not data we have access to.”

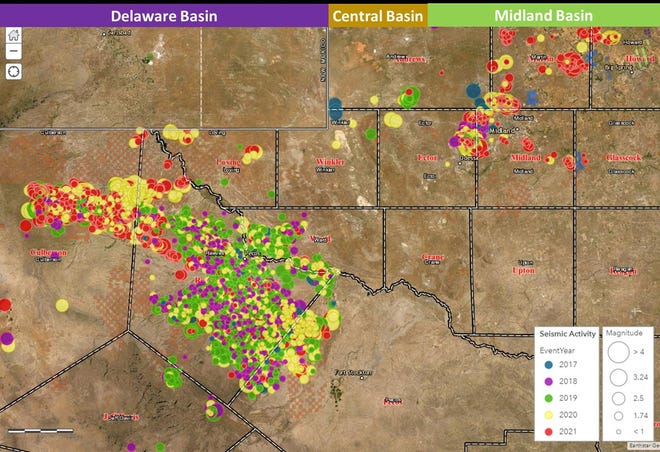

Earthquakes getting worse in Permian Basin

A June report from Rystad Energy, an oil and gas research firm, found earthquakes in the U.S.’ major oil and gas regions increased each year since 2017 with events above a 2 magnitude on the Richter Scale quadrupling in 2020.

The tremors were forecast to increase further by the end of this year, the study warned, if drilling methods continue at the same pace.

The study analyzed seismicity in New Mexico and Texas, along with other major oil-producing states Oklahoma and Louisiana, reporting 242 such earthquakes with a 2 magnitude in 2017, rising to 491 in 2018, 686 in 2019 and 938 in 2020.

In the first five months of 2021, 570 events were recorded, meaning last year’s number could be surpassed before the end of this year.

More:Report: Oil and gas fracking in New Mexico could contaminate water with ‘forever chemicals’

More:Houston-based oil and gas wastewater company expands operations, addressing seismic concerns

Not only are the events becoming more frequent, but the magnitude was also increasing, with 11 seismic events recorded with a magnitude more than 3.5 this year.

There were only six such earthquakes in 2018 and 2019, the report read, and 14 through all of 2020.

Earthquakes registering at a 2 or 3 on the Richter Scale can be felt, but rarely cause damage, per the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), while a magnitude of 5 can cause some light damage.

More:Oil and gas to face stricter wastewater oversight if New Mexico Senate bill passes

More:Waste to water: From basin to basin, oil and gas water dilemma grows as production booms

As earthquakes increased, Rystad reported the volume of injected water also rose from 7.7 billion barrels in 2011 to 11.3 billion barrels by 2020.

In the Permian Basin, data from TexNet, which tracks seismic activity in Texas showed 5,242 seismic events in 2021 so far this year among counties in the Delaware Basin, the most active sub-basin of the Permian.

Most of the events were no higher than a magnitude of 2.

But compared with 1,577 in 2017, the data showed an about 233 percent increase in seismicity in the 11 counties.

More:WPX Energy settles with Carlsbad family for oil and gas wastewater spill in January 2020

More:Work continuing in New Mexico to reuse oil and gas wastewater in other sectors

Culberson County, located almost on the Texas-New Mexico border led the region with 4,120 tremors so far this year, compared to 12 in 2017.

Culberson was followed by Reeves County, also on the the state’s border, with 744 quakes and Scurry County with 196.

New Mexico regulators push for alternatives

Jason Jennero, chief executive officer with Breakwater Midstream – a Midland-based water recycling company – said the trend was troubling and indicative of the need for an alternative to disposal injection.

He said recently, the area began seeing the occasional 4 or 5 magnitude earthquakes, a sign that the problem could be getting worse.

Most recently, the USGS reported a 4.3 quake in Toyah, Texas in Reeves County on July 28 and 10 others with a magnitude of 3 or higher in the past month in the Delaware in Texas and New Mexico.

More:Outlawed: Oil and gas spills now illegal in New Mexico. Industry supports rule change

More:198 oil and gas wells found abandoned near Carlsbad Caverns National Park

A 4.0 magnitude quake was reported in Malaga, New Mexico, south of Carlsbad, on July 19, and a 3.2 and 3.4 were reported at Whites City near Carlsbad Caverns on Aug. 2 and July 8, respectively.

The rest were in Texas.

Since January, the USGS reported 102 earthquakes at a 3 magnitude or higher in the region, mostly on the Texas side, with the biggest of the year so far, a 4.5 magnitude reported in Whites City in on March 16.

In all of 2020, the USGS reported 82 such earthquakes in the same region, and just 19 and 15 in 2019 and 2018, respectively.

“We’re getting 4s and 5s,” Jennaro said. “It’s beginning to become a real deal. “Clearly there are a lot of pipelines that come from New Mexico over the border.”

“I think it’s fair to ask the question of if New Mexico is exporting earthquakes. These disposals have sent millions of barrels of New Mexico water down hole.”

He pointed to almost 200 saltwater disposal (SWD) wells within 10 miles of the New Mexico-Texas state line, arguing the data indicated a connection between the wells and growing seismicity.

“It’s been connected predominantly to saltwater disposal injection. It’s not controversial anymore that there’s a pretty strong relationship,” Jennero said. “You can’t look at the data and not see that there’s something going on.”

Those wells in Texas could be used by operators over the border more frequently as Sandoval said the state encourages other methods of water management in New Mexico.

More:Educators in New Mexico call for shift away from ‘unstable’ oil and gas revenue for schools

More:How Big Oil keeps a grip on New Mexico – with the help of a major lobbyist

“We hear that operators have operations on both sides of the border. It’s definitely possible that water is being injected in Texas that originated in New Mexico,” Sandoval said. “In general, we are encouraging more recycling of produced water.”

Recycling the water instead of injection can be expensive for operators, Rystad reported, potentially rising to $1 billion for U.S. oil and gas operations by the end of the year.

And the Permian Basin could be the most affordable place to do it, said Shale Analyst Ryan Hassler.

More:Oil and gas rigs steady in Permian Basin, New Mexico keeps 2nd place in crude production

More:Permian Basin leads U.S. in oilfield emissions, could be ideal for underground carbon storage

“The costs can vary per region, but the Permian Basin has very competitive economics compared to other areas,” he said.

To offset annual projected growth of disposed water as the shale industry appears poised to boom in the coming years, Rystad estimated treated water must increase from 1.5 billion barrels in 2020 to 1.7 billion barrels this and next year and to 1.8 billion barrels in 2023.

By 2024, the analysis estimated the need to dispose of oil and gas wastewater will grow to 12 billion barrels.

More:Ozone pollution at Carlsbad Caverns comes from oil and gas. State readies emissions rules

More:Undocumented oilfield workers struggle in New Mexico. Heinrich pushes for energy transition

Aside from earthquakes, Hassler said disposing of the water rather than treating it can tax freshwater sources, especially in the desert region in West Texas and southeast New Mexico.

“Earthquakes are not the only environmental issue caused by water disposal. Fresh water sourcing in arid regions of West Texas and New Mexico threaten the water supply of local communities and essential agriculture activities, while environmental concerns surrounding the chemical composition of produced water serve only to fan the flames of public antipathy,” he said.

By the end of 2022, the Permian Basin – both in the western Delaware and eastern Midland sub-basins could reach 40 to 43 percent of recycled water used in fracking.

And Jennero hoped to be at the forefront of meeting the basin water midstream needs.

Recycle and reuse

Breakwater recently completed construction of its Big Spring Recycling System in Martin County near Midland, Texas, adding to the nine recycling facilities it operates in the region.

The company’s total capacity is about 300,000 barrels per day of produced water treatment and can distribute up to 360,000 barres per day.

“We’ve built the largest recycling system in Texas. We’re actually building water pipelines into the seismicity to try to move it away from the seismic clusters and prevent it from going downhole,” Jennero said. “There’s just an enormous amount of seismicity.”

He urged operators to avoid disposal injection and work to use more treated water to avoid increasingly dangerous seismic activity.

“Those earthquakes are starting to move toward more populated areas. One of the concerns is a lot of those buildings were built in the 30s or 40s,” Jennero said. “They weren’t constructed to withstand California-style earthquakes. This has the potential to cause some material damaged.”

In New Mexico, Sandoval said that as a regulator the OCD can only rely on its permitting requirements to space disposal wells far enough apart to avoid triggering earthquakes.

More:New Mexico hopes for oil and gas windfall as nation recovers from COVID-19

More:Joe Biden reinstates federal oil and gas methane rules rolled back by Trump

OCD records show the state is making progress as 54.5 percent of water used in oil and gas is recycled, and only 6.1 percent of the water used in fracking is freshwater.

The agency saw induced seismicity linked to water disposal on the New Mexico side of the border in Eddy and Lea counties, Sandoval said – the state’s two biggest oil and gas producers.

“We don’t want any earthquake activity that could threaten property or people in any way,” Sandoval said. “The larger the earthquake, the larger the potential for impacts so we want to mitigate that.”

Adrian Hedden can be reached at 575-618-7631, achedden@currentargus.com or @AdrianHedden on Twitter.