A bill introduced in the U.S. Senate this week could impact future nuclear projects in New Mexico where a private company hopes to build a facility to store some of the most highly-radioactive nuclear waste in the U.S.

U.S. Sen. Edward Markey (D-Mass.) and Rep. Mike Levin (D-CA.) introduced the Nuclear Waste Task Force Act on Sept. 28 which would establish a task force tasked with studying amendments to the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 to remove environmental exceptions for nuclear waste, creating a consent-based program for siting facilities.

If passed and depending on the recommendations of the task force, this bill could prove a roadblock to projects like one proposed by Holtec International to build a temporary storage facility for spent nuclear fuel rods in southeast New Mexico.

More:Texas sues federal government to block nuclear waste facility along New Mexico border

The project would hold up to 100,000 metric tons of the waste temporarily while a permanent repository is developed. Such a final resting place for the waste does not exist in the U.S. as a site at Yucca Mountain, Nevada was blocked by state lawmakers and defunded under the administration of former-President Barrack Obama.

The Holtec project drew widespread opposition from New Mexico leaders, including Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, Attorney General Hector Balderas and Commissioner of Public Lands Stephanie Garcia Richard.

But the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) recommended earlier this year that a license be issued to Holtec despite state concerns, and recently issued a license to a facility in West Texas proposed by Interim Storage Partners that was also opposed by leaders in that state.

More:Texas votes to ban high-level nuclear waste storage. Could New Mexico do the same?

If passed, the bill was intended to put more power into the hands of states as current law does not require the federal government gain consent at that level when siting nuclear facilities.

“When it comes to the storage of nuclear waste, siting decisions must be rooted in geological science, not political science,” Markeys said. “Enabling consent-based storage is the key to developing real, practical solutions for the long-term storage of nuclear waste. This nuclear waste task force will play a critical role in determining how to make that happen.”

And New Mexico does not consent to Holtec’s proposal, said Don Hancock, nuclear waste program manager at Albuquerque-based watchdog group Southwest Research and Information Center.

More:WIPP: Air system rebuild at Carlsbad nuclear waste site two weeks ahead of schedule

He said opposition from state leaders and public comments gathered during the NRC’s licensing process showed the majority of New Mexicans were not in favor of the facility.

“If you look at the public comments, most of the people have opposed this. One of the flaws is the NRC said we don’t care,” Hancock said. “NRC is correct when they say the law doesn’t require them to get consent from a state to license these facilities.”

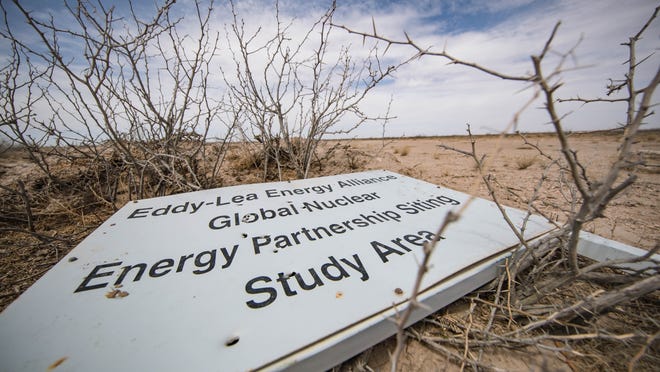

Local government leaders from the cities of Carlsbad and Hobbs and Eddy and Lea counties – where the site would ultimately be built – voiced support for Holtec.

More:WIPP: New panels to dispose of nuclear waste

The Eddy-Lea Energy Alliance, a consortium of the four local governments that owns the land and courted Holtec, promoted the project to create jobs and diversify the economy in a region heavily reliant on oil and gas extraction.

Even if the federal license is ultimately issued, Hancock said the state could still block its operation by denying permits such as for access to water or other utilities as has occurred in other states where nuclear waste repositories were proposed.

With a consent-based process, Hancock said the state and federal government would work together to develop the site and avoid future conflicts.

More:NRC: Court lacks authority in New Mexico lawsuit against nuclear waste site

“Every state that’s been considered for high level waste repositories have said no,” he said. “That’s not always the end of it. Existing law says Yucca Mountain is the first repository. Law doesn’t give Nevada the right to consent, but they’ve said they’ll never consent, and they’ve stopped that project.

“There are certain powers the federal government does not have. Insofar as the federal government has the authority for nuclear waste disposal, it does not have the authority for other things needed for a repository.”

Levin argued the bill would enable the federal government to move past conflicts with states over nuclear waste sites and toward a solution for what to do with the nation’s nuclear waste.

More:Nuclear waste facility near Carlsbad sees COVID-19 surge as infections rise in New Mexico

Spent nuclear fuel is presently stored mostly on-site at reactor sites across the country, mostly near large bodies of water and dense population areas.

Everyone agrees the waste shouldn’t stay where it is forever, and Levin said the task force could prove invaluable in finding a path to disposal.

“We must advance a consent-based path to long-term disposal and exploring this pathway to consent is a critical step in that process,” he said. “I know that doing so can move the ball forward on that step and help solve our storage challenges once and for all.”

Adrian Hedden can be reached at 575-618-7631, achedden@currentargus.com or @AdrianHedden on Twitter.