REGION — San Diego area water prices and regulations don’t relate directly to the growing scarcity of water in the drought-stricken Colorado River Basin, from which the region imports about half its supply.

As The Coast News reported earlier in April, the San Diego County Water Authority is developing a water shortage contingency plan, though not implementing it, despite drought and low levels in major reservoirs along the Colorado’s path.

“There is no plan or expectation that the (contingency plan) will be implemented this year,” the Water Authority’s Jeff Stephenson said Monday.

“Generally speaking, price isn’t used as a mechanism to ration water in California, nor to identify its scarcity, because of the system of water rights that we’ve adopted over time,” said Kurt Schwabe, chair of environmental economics and policy at UC Riverside.

The Water Authority sets prices annually based on forecasts, but “in real time, we can’t adjust the price,” Stephenson said. Additionally, because of Proposition 218, a 1996 voter initiative, “we can only charge the cost to recover our expenses to deliver the water.”

“Water rates are very devolved at a very local level,” Schwabe said. “In that sense, they’re all thinking about their own constituency, even though water is connected” across agency jurisdictions.

All that to say, water doesn’t strictly follow the principle of supply and demand, whereby something generally becomes more expensive when there’s less of it to go around.

Instead, accumulated laws, regulations, court rulings and contracts known as the “Law of the River,” pledge California a certain volume from the Colorado River. Under one agreement, California’s rights take priority, such that it may continue drawing its full allocation, even if Arizona and Nevada must cut back in order not to deplete Lake Mead below a critical level.

“We really don’t talk in terms of ‘scarcity,’ but we do talk in terms of ‘shortage,’” Stephenson said. “Shortage” in this vernacular doesn’t describe water’s objective availability in the total marketplace. Rather, it means an agency’s allotted supply wouldn’t meet expectations due to cutbacks triggered administratively, such as by a governor’s executive action.

For instance, while Gov. Gavin Newsom recently declared a regional drought emergency in Sonoma and Mendocino counties, San Diego County remains in the clear.

Because of its high priority water rights, the San Diego County Water Authority’s Colorado River “supplies are largely insulated from cutbacks,” Authority spokesman Ed Joyce said previously.

However, that San Diego County isn’t experiencing a contingency-triggering “shortage” doesn’t mean water isn’t in shortened supply in the places it’s imported from.

The whole length of the Colorado River — through Colorado, Utah, Arizona and Nevada — is experiencing “extreme” to “exceptional” drought conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, a government-university partnership.

The Law of the River’s divvying to Western states “was based on flow data collected between 1905 and 1922, a period that contains the highest long-term annual flow volume in the 20th century,” Arthur Littleworth and Eric Garner write in their 2019 book “California Water,” now in its third edition. However, subsequently, “flows have been much lower than expected,” resulting in “over-allocation” to rightsholders.

Due to “a warming trend in the Colorado River basin … water supplies are expected to decrease further,” the authors write.

Asked whether the Colorado is being used sustainably, Stephenson said: “That’s to be determined,” though “the states are all working on plans constantly to make sure that the Colorado River is sustainable.”

“In 2020, total (San Diego County) regional use of potable water was about 30 percent less than it was in 1990, even though the regional population grew by 35 percent,” according to the Water Authority’s web site.

But San Marcos’ Jack Paxton, a professor of agricultural, consumer and environmental sciences retired from the University of Illinois, takes a harder tone.

Colorado River rightsholders are “absolutely not” consuming water sustainably, he said. Whereas the Water Authority “should be looking at the whole Colorado River Basin,” he described its water use philosophy in general as “myopia” and “beggar thy neighbor.”

For example, he pointed to a 2016 Colorado state law banning the use of rain barrels as a conservation measure to collect rainwater from certain residential rooftops. The law declared water “subject to the doctrine of prior appropriation,” ordering the state engineer to report whether “small-scale residential precipitation collection … has caused any discernable injury to downstream water rights.”

California public agencies “don’t price water itself, it’s considered a free good,” Paxton said. Nevertheless, he thinks the Water Authority should “put out a drought advisory” encouraging residents “to be more water frugal.”

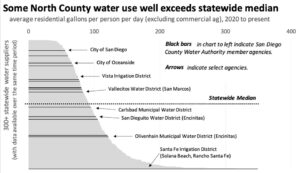

San Diegans’ per capita residential water use varies considerably countywide, with certain North County districts clocking in above the statewide norm. Of 331 statewide water agencies reporting over a comparable time period, the Santa Fe Irrigation District posted the highest per capita use by far, nearly four times the statewide median, according to The Coast News’ analysis of state government data. That district, a Water Authority member, serves Rancho Santa Fe and Solana Beach.

“We have a lot of large properties and some of those properties have agriculture and livestock on a residential meter, so they are included in residential use,” said Santa Fe Irrigation District spokeswoman Teresa Penunuri.

Carlsbad Mayor Matt Hall, Encinitas Councilman Joe Mosca and Escondido Councilwoman Consuelo Martinez, who are among North County’s representatives on the Water Authority’s governing board, didn’t respond to several requests for comment.