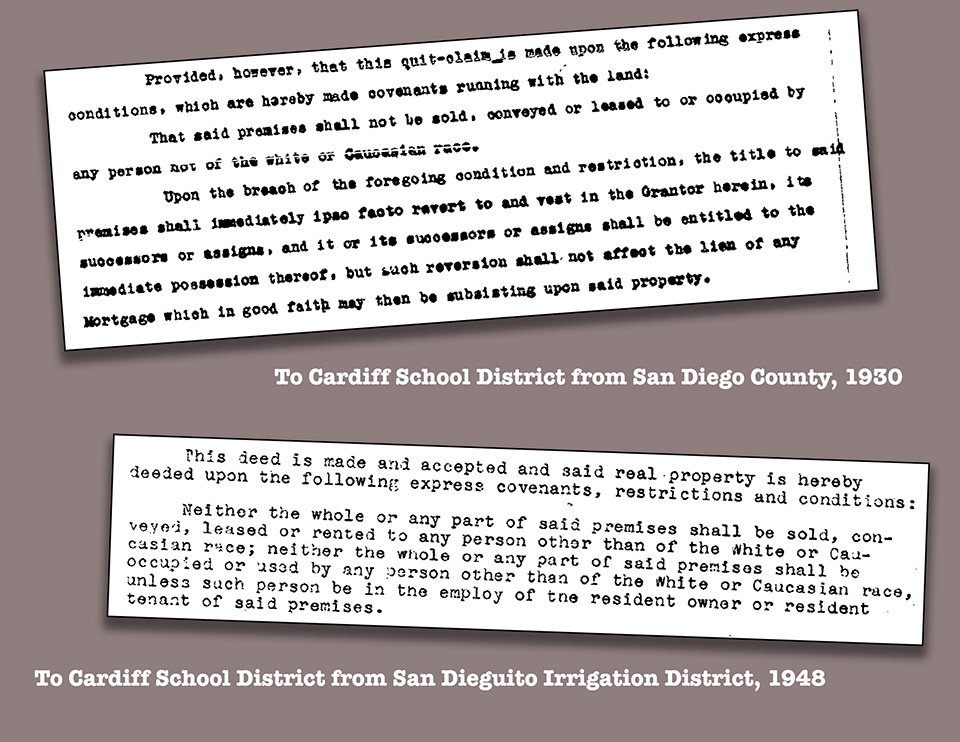

It was unsettling to learn recently that property in Encinitas had used exclusionary racial covenant language in property transfer documents that prohibited anyone other than White people from owning, renting or using property in Cardiff.

One of the quitclaim deeds states, “That said premises shall not be sold, conveyed or leased to or occupied by any person not of the white or Caucasian race.”

Given that this was a transfer of property to a school and it says the land can’t be “occupied by” anyone non-White, it’s natural to wonder if this was an attempt to keep schools segregated.

Additionally, the language stating that the land could not be “sold, conveyed or leased” to anyone non-White means that if the school had closed its doors and the property was sold off, the buyers were intended to be only White people and not minorities.

What do we make of this? I know there are many Caucasians, including my Cardiff family, who probably have an instinctive, well-meaning response that these deeds are relics from decades past that don’t affect the present day.

After all, anti-discrimination laws and changing societal norms have replaced old prejudices.

Furthermore, language like this is both illegal and immoral.

But taking a moment to reflect on how the foundations of our city set the standards, which still influence our current debates and dialogues, leads to a more unsettling place.

It’s never easy wrestling with an uncomfortable history.

When there are explicit policies from government institutions that solidify and entrench segregation, those patterns can linger and become normalized unless they’re addressed head-on.

Currently, the City of Encinitas is 78% White, 14% Hispanic/Latino and 0.8% Black.

Similarly, the 750 students in the Cardiff School district are now 71% White, 19% Hispanic/Latino, and 0.3% Black.

Of course we know that anyone of any race could now legally move here and attend Cardiff School or become a resident of Encinitas.

Court cases have interpreted the 14th Amendment as prohibiting any type of racial covenant language.

But it’s also true that the majority of families who have had the chance to live and go to school here for many generations have been largely White, and have enjoyed the benefits and privileges that come with that — whether they be financial gains from investments in a home, high educational quality, incomparable outdoor and recreational opportunities, and top-notch community programs and services.

Communities have been built here, while other communities have not had the chance to create roots here.

It’s very expensive to buy a home in Encinitas, where the median home price is now $1.4 million. We’re also the city with the lowest percentage of apartments of all 18 cities in San Diego County.

The increasingly challenging financial barriers for upward mobility into Encinitas and other higher-opportunity communities are real.

For me, seeing these obsolete racial covenant deeds in my hometown reinforces the need for intentional actions and approaches to create a city that is diverse, desegregated and committed to equity.

You may have heard about the City of Encinitas’ Equity Committee, which aims to discuss city policies and propose suggestions that will create more just outcomes.

At the county’s transportation organization, SANDAG, we are also working toward a transportation system with the same goals.

This year the SANDAG board, which I chair, unanimously adopted the following statement as part of its commitment to equity statement:

“We hold ourselves accountable to the communities we serve. We acknowledge we have much to learn and much to change; and we firmly uphold equity and inclusion for every person in the San Diego region.

This includes historically underserved, systemically marginalized groups impacted by actions and inactions at all levels of our government and society.”

This reference to “action and inaction at all levels of government and society” is particularly important.

Being clear-eyed about our own history is an important step in creating a more inclusive and just world.

And it will always be a work in progress.

If you’re interested in these topics, I’d highly recommend these two books, which have impacted my thinking: “The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein and “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander.

Catherine Blakespear is serving her 5th year as Mayor of the City of Encinitas. She can be reached at [email protected]